THANK YOU FOR VISITING SWEATSCIENCE.COM!

As of September 2017, new Sweat Science columns are being published at www.outsideonline.com/sweatscience. Check out my bestselling new book on the science of endurance, ENDURE: Mind, Body, and the Curiously Elastic Limits of Human Performance, published in February 2018 with a foreword by Malcolm Gladwell.

- Alex Hutchinson (@sweatscience)

***

My wife is out of town at the moment, which means I’m doing lots of running on my own. Plenty of time to ponder the meaning of life — and, when I get tired of that, to count my footsteps. Sparked by interesting discussions with the likes of Pete Larson from Runblogger and Dave Munger from Science-Based Running, I’ve been wondering what my own cadence is like — particularly in light of widespread belief in the magic of 180 strides per minute. Over the past few weeks, I counted strides for 60-second intervals at a variety of paces. Here’s what I found:

Most surprising to me was (a) how consistent my cadence was when I repeated measurements at the same pace, and (b) how much it changed between paces: from 164 to 188, with every indication that it would decrease further at slower paces and increase further at faster paces. This certainly confirms what Max Donelan, the inventor of a “cruise control” device for runners that adjusts speed by changing your cadence, told me earlier this year: contrary to the myth that cadence stays relatively constant at different speeds, most runners control their speed through a combination of cadence and stride length.

Most surprising to me was (a) how consistent my cadence was when I repeated measurements at the same pace, and (b) how much it changed between paces: from 164 to 188, with every indication that it would decrease further at slower paces and increase further at faster paces. This certainly confirms what Max Donelan, the inventor of a “cruise control” device for runners that adjusts speed by changing your cadence, told me earlier this year: contrary to the myth that cadence stays relatively constant at different speeds, most runners control their speed through a combination of cadence and stride length.

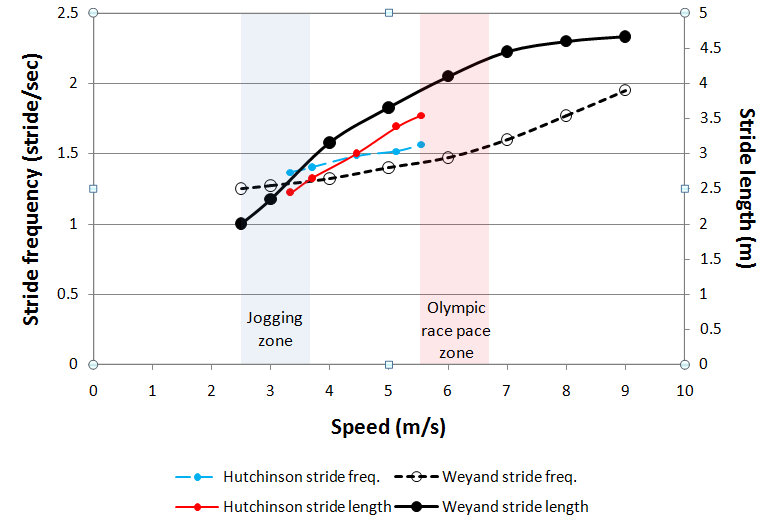

So the next question is: am I a freak, running with a “bad” slow cadence at slower paces, but a “good” quick cadence at faster paces? To find out, I plotted my data on top of the data from one of the classic papers on this topic, by Peter Weyand:

The graph is a little busy, but if you look closely, you’ll find that my data is slightly offset from the Weyand data, but has essentially identical slope. So compared to a representative example of Weyand’s subjects, I have a slightly quicker cadence and shorter stride at any given speed, but my stride changes in exactly the same way as I accelerate. So I’m not a freak: the fact that my cadence increased from 164 to 188 as I accerelated from 5:00/km to 3:00/km is exactly consistent with what Weyand observed.

One key point: I’ve highlighted two key “speed zones.” One is the pace at which typical Olympic distance races from the 1,500 metres to the marathon are run at. This is where Jack Daniels made his famous observations that elite runners all seemed to run at 180 steps per minute (which corresponds to 1.5 strides per second on the left axis). The other zone is what I’ve called, tongue-in-cheek, the “jogging zone,” ranging from about 4:30 to 7:00 per kilometre. This latter zone is where most of us spend most of our time. So does it really make sense to take a bunch of measurements in the Olympic zone, and from that deduce the “optimal stride rate” for the jogging zone?

This isn’t just a question of “Don’t try to do what the elites do.” If Daniels or anyone else had measured my cadence during a race, it would have been well above 180. But at jogging paces, it’s in the 160s. I strongly suspect the same is true for most elite runners: just because we can videotape them running at 180 steps per minute during the Boston Marathon doesn’t mean that they have the same cadence during their warm-up jog. In fact, that’s a pretty good challenge: can anyone find some decent video footage of Kenyan runners during one of their famously slow pre-race warm-up shuffles? I’d love to get some cadence data from that!

Of course, this doesn’t mean I don’t think stride rate is important. I definitely agree with those who suggest that overstriding is probably the most widespread and easily addressed problem among recreational runners. But rather than aspiring to a magical 180 threshold, I agree with Wisconsin researcher Bryan Heiderscheit, whose studies suggest that increasing your cadence by 5-10% (if you suspect you may be overstriding) is the way to go.

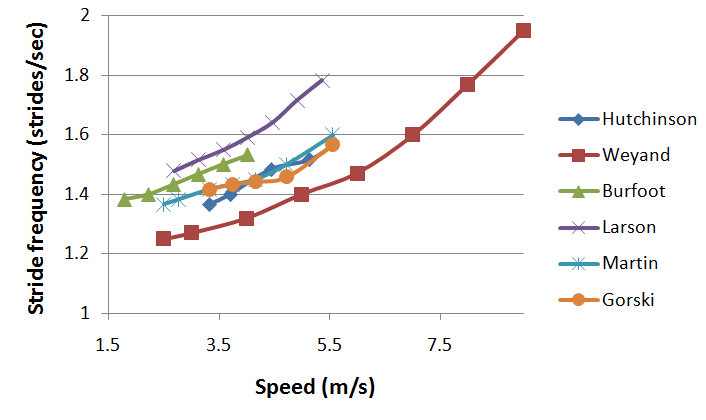

[UPDATE: Make sure to check out the interesting discussion in the comments section! Also, Amby Burfoot did his own cadence test and posted the data. I’ve added it to the graph below to show how it compares to my own and Weyand’s data. Feel free to try it out on your next run, and I’ll add your data to the graph too!]

That slope looks pretty consistent!

[Another update: I’ve added Pete Larson’s data from his excellent post on the topic. Now there’s a guy who knows how to take serious data! Plus data from Brian Martin and Mark Gorski.]

Pardon if this is a very dumb question: I’ve always attributed the fact that I’m SHORTER than most humans (we have some LPs on the uni campus where I have my second job and I’m a few inches taller than them rather than a foot +) to the reason I have to make “so many” steps compared to the person jogging next to me. Surely, when I’m attempting to go faster, my stride increases as I’m “reaching out” in front and propelling myself farther/ harder off the back leg.

Won’t I “always” have more strides frequency due to stride length being lesser (again, due to being stumpy)? And isn’t this the same for anybody less than average (perhaps quite a bit less than average)?

Same type of results for me between paces of 7:10 and 13:00 per mile. I thought I was the only one like this after reading all the articles that you should strive for 180 regardless of pace. I’m 52 and ran 5Ks in low 15s in my early 20s. I wish I knew what my stride rate was back then.

As far as a film clip, there’s Haile Gebrsellasie bio film “Endurance” – a few clips (very limited) of Kenyans warming up before the Atlanta 10000 final, plus extended footage of Haile training back home – a rather long series of side-view footage of him alone.

Alex: Great stuff. Glad you did this. Agree that most of us probably follow a curve like yours. So I guess the next logical question is, What’s the ratio of your stride length (or speed) to your stride frequency? I suppose any of us could determine that from the above, but you could also do it and save us lazy types the work. Needless to say, we also want to know if your foot strike changed with changes in pace. Though somehow I doubt you managed to high-speed video your foot strike while counting strides and measuring pace. 🙂

I am able to keep my cadence at the 180 range regardless of speed… It is the intensity of the push off that makes the difference . Try it on a treadmill too and u can seer that cadence can stay high regardless of speed .

Great post — I love seeing good work on cadence.

This shows that if you consciously focus on increasing pace, you will accomplish this by naturally increasing both stride length and frequency. But my question is, what happens if your focus is on stride frequency, rather than pace? In other words, if you consciously focus on increasing stride frequency, how will this impact stride length and pace?

Recently, I’ve been trying to increase my speed by training with a metronome, and although I have found that a faster cadence leads to a somewhat faster pace for me, the increase hasn’t been proportional, leading me to believe that my stride length is actually shortening slightly as I increase stride frequency. I haven’t taken the time to carefully measure any of this yet, though. This observation meshes with the standard advice given to overstriders, which is to increase cadence in order to shorten the stride length.

Re-reading the “cruise control” post that you linked, I see that it quotes Max Donelan claiming that increasing stride frequency will also lead to increased stride length. I wonder whether I am mistaken about my own experience — I guess it’s time for me to hit the track and get some real measurements.

Like Elise, my cadence is very steady and just a bit over 180. However, this seems to be the case only when I am NOT pushing off well. When I engage the entire leg in the running motion and therefore push off well, my cadence DOES vary. I did the engage-the-entire-leg experiment yesterday and in the process disabused myself of my long-held notion that my stride rate never varies. I am curious to see what my stride does at a full range of paces with proper push-off and will no doubt go back to counting steps next time I’m on the treadmill!

@Amby Burfoot

I speculate that the author’s foot strike shifts forward with increased pace. I know mine does simply as a matter of economy. At quicker paces and faster cadence, it becomes more efficient to reduce ground contact time, so I necessarily shift to a nimbler forward strike. The main problem with general prescriptions about form is that it’s impossible to know how economical they are for an individual. Changes that come through training are necessarily tested for efficiency and recursively refined for your body and its idiosyncrasies. I submit that this is a more fruitful path to improved form for an individual than analysis of elites.

I have kept track of ratio of cadence/stride length for about 6 months. Ave is 19.47 with St Dev of 1.37. With this ratio, faster paces have lower number for me. It might be interesting to plot that ratio with pace to see what it looks like. I have also tracked stride length/height. Ave is 0.68 with St Dev 0.06. Faster paces have a higher number. Amby – if you see this it is Ken S from your days in New London. I was at CGA from 77-81.

I just did a short treadmill experiment, counting my stride frequency while

accelerating from 4 mph to 9 mph. Sadly, I’m too old, injured, and

out of shape to go faster.

I set the treadmill incline to 1 percent, wore thick training shoes,

and ran for a minute at each speed. I counted my strides from :15 to

:45 of each minute, and doubled the total to get my per-minute frequency.

I am 6′ 0″ tall, and consider myself a short-striding shuffler.

Results:

4mph, 15:00/mile >>> 166 strides/min

5mph, 12:00/mile >>> 168

6mph, 10:00/mile >>> 172

7mph, 8:30/mile >>> 176

8mph, 7:30/mile >>> 180

9mph, 6:40/mile >>> 184

This is a very simple experiment to duplicate if anyone else would

like to try it and post their results.

Hi Ken: I just saw your note, but didn’t understand units in your first ratio. You can contact me direct at amburf@gmail.com

For once I do not think that you have done your research properly:

You are not comparing yourself to “Weyand’s subjects” but to “a representative subject” (text under fig. 2 in his paper). I would rate “a representative subject” close to anecdotal evidence. Is a person that is able to run at a speed of 9 m/s “representative” and comparable to you? And is the procedure of suspending the runner in the air over a speeding treadmill and just recording 8 steps comparable to the running that you are doing?

Didn’t you notice that Heiderscheit’s subjects were running by own choice with an average cadence of 172.6 steps per minute at an average speed of 2.9 m/s already before the manipulation and that increasing their step rate by 10 % brought it up to 190?

If you follow your own suggestion at the end of this blog by increasing your cadence by 10 % your cadence of 164 at your slow speed will be exactly 180!

Is your wife normally proofreading your articles?

Thanks for all the great comments and feedback, everyone! Some quick thoughts:

@Lily: “I’ve always attributed the fact that I’m SHORTER than most humans…” Absolutely. It seems totally obvious to me that body size makes a difference — and not just height, but also ratio of leg length to body length and so on. It’s ludicrous to think that at any given pace, someone who is 4’6″ should run with same stride length and cadence as someone who is 6’6″.

@Ken and @Kent: thanks for the comments!

@Elise: “I am able to keep my cadence at the 180 range regardless of speed…” Well, sure. So am I. But the question isn’t CAN I do it, it’s SHOULD I do it?

@Michael: You make some great and important points. We can ask two very different questions:

(1) What happens to my cadence when I consciously increase my speed?

(2) What happens to my speed when I consciously increase my cadence?

In this post, I focused on the first question — I wanted to know what cadence I naturally settle into at different speeds.

You’ve been experimenting with the second question: increasing your cadence, and then watching to see what happens to your speed (and consequently your stride length). What you’ve observed — that your stride length decreases — is exactly what people are hoping for when they recommend increasing cadence, since a shorter stride means you’re less likely to be overstriding. And that’s consistent with Bryan Heiderscheit’s work. You’re right that Max Donelan’s experiments apparently suggest the opposite. I suspect it has a lot to do with how the experiment is set up, and whether runners have the sense that they’re supposed to speed up as they increase cadence (as in Donelan’s cruise control experiments) or whether they know they’re supposed to maintain the same pace (as in Heiderscheit’s). We respond to the cues we’re given, to some degree.

@Ken: “I have kept track of ratio of cadence/stride length for about 6 months… With this ratio, faster paces have lower number for me.”

Interesting. It’s not immediately clear to me what that ratio tells us — I’ll have to think about it!

@Jørn: Thanks for the comment, and for pointing out that Weyand’s data is from a single subject rather than an average — I’ve fixed the text.

As for the rest of your comment: first of all, I’m not sure why you felt the need to be so rude. Second of all, I don’t think you understood the point of my post. I am perfectly aware that adding 10% to 164 gives 180. My goal wasn’t to teach basic arithmetic, it was to explore whether runners should expect to stay at a single cadence regardless of their speed. It’s pretty clear, even from your own comment, that the answer is no.

Sadly, gravity is wreaking havoc with my stride rate.

@alex

Dear Alex,

I certainly did not mean to be rude. My sincere apologies! Danish humour sometimes appears that way to others 🙂

Secondly I think I understood your point perfectly – but I disagree with it and I also partly disagree with your comment to me (that the data shows that runners should not stay at 180 steps).

If I appeared rude it was not because of you but because of Weyand’s article. The point I was trying to make was that this article applies only to runners suspended over a speeding treadmill and running for a few seconds (8 steps) without any wind resistance and thus does not apply to any practical running. The article does not even hold water by itself: Their conclusion “that human runners reach faster top speeds not be repositioning their limbs more rapidly in the air” can only be based on videos and accellerometers attached to limbs – which they did not use and also they disregard the effect of running style and disregard the horizontal forces on the force plate – I could go on…

But why argue when you can experiment? I have been heavily pounding with a very low cadence most of my life. When I started learning ChiRunning 5 years ago I almost painfully brought up my cadence to 173 and had myself convinced that I could not go any further. I got exhausted of even 174 until I read Heiderscheit’s paper in November 2010. Then overnight I increased my cadence to 180. It felt hard at first but after two months running at that cadence it felt natural. I just concluded an experiment where I at 6 occasions ran through the same course (4.17 km) at the same speed three times. The first as a warm-up and the next as tests at either 173 or 180. I measured the average pulse rates as 139.2 and 139.9 respectively. The difference is non-significant. But what was more important to me was that I perceived the effort of running at 173 much higher than running at 180. You may see my complete experiment here:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1mVF9KMh6w1IrFAY0U3izLiJeBuWQ7GJrpwecsCw4uls/edit?hl=da

For the record I am an old man – close to 65 – weighing 75 kg because of course build means something too.

Back to the data from the “representative subject”: If you follow Heiderscheit’s recommendation and increase the subjects low speed cadence to 180 it appears that you can stay at this cadence until the Olympic Pace Zone. From there I admit that the cadence has to increase, because of anatomical limitations. I also increase my cadence at high speeds when running HIT where my speed gets above 6 m/s.

So the best single advice you can give to “runners” (disregarding sprinters and Olympic athletes) is to bring their cadence (up) to 180 and stay there. Use a metronome or an mp3 cadence file to get there. It might take a couple of months to get comfortable at the cadence but give it a try. If it feels very difficult then try to go even higher and then drop back to 180. Why don’t you keep an open mind and try too?

@Jørn: Thanks for the detailed response. The reason I thought (and still think) that you’re missing the point of my post is that both your comments have focused on proving to me that’s it possible to run at 180 steps per minute at a slow pace. This is a trivial point. Of course you can! I can too! The real question is: is there any reason that we SHOULD?

The standard response I’ve been given when I ask that question is: Jack Daniels measured the cadence of Olympic distance runners during their races, and they all had cadences of at least 180, therefore this must be a good thing. The flaw in that logic is that it presupposes that Olympic runners racing with a cadence of 180 must also keep that cadence when they jog at a slow pace more comparable to how recreational runners run.

In order to test in a limited way whether this is likely, I measured my own cadence at a variety of paces. Like the Olympic runners, my cadence was above 180 at Olympic race paces. However, at “jogging” paces, my cadence was significantly lower. Therefore, I conclude that we shouldn’t draw conclusions about the “optimal” jogging cadence based on measurements of how Olympic runners run during races. To check that I wasn’t a complete outlier, I plotted my data atop that of the “representative” sample from Weyand’s paper. That was the point of my post.

As for Heiderscheit’s paper, I agree with his recommendation that you should increase your cadence IF YOU’RE OVERSTRIDING. This could be true if you have a cadence of 150, 170, or even 190, depending on factors such as how long your legs are and how fast you’re running. But, like Heiderscheit, I see no evidence whatsoever to suggest that 180 has any privileged position as a “minimum threshold” to which we should all aspire.

As with any running-related journalism, I hope the truly novice or recreational runners are cautious with this topic. This discussion focused on advanced, experienced runners. Alex, your suggest that ideal cadence can only come from experience and experimentation is the best take away for the new runner. For what it’s worth, I have introduced a few hundred to the joys of running and, without fail, cadence has been the number one key to transitioning them comfortably to running 5k. And the cadence I teach is 180.

Thanks for the comment, Geordie — your points are very well taken. Like any persistent rule of thumb, part of the reason the 180 rule has stuck around is that it can be very effective for many people. As I mentioned in the post, I suspect overstriding is the most common error among new runners — and telling people to aim for a high cadence is a very straightforward and effective way of curing that problem (or avoiding it altogether). Keep up the great work!

I agree with Jorn, i use the pose method of running and find 180 bpm to be comfortable and i can’t imagine a heel striker being comfortable at that pace, I too use a metronome for running on my ipod. Yes you have to work at it. it isn’t easy. but using pose method, mastering the POSE/FALL/PULL and practicing the drills will help.That said it a complete over hall of technique if you wish to run POSE. lighter shoes, racing flats, getting barefoot at least twice a week, practicing drills, strength training especially for the lower limbs. seriously i can’t wait to run and run with ease.nice article.thanks

@alex

Just a final note (I certainly do not want to keep you busy answering me! but thanks for your feedback). Sometimes I miss brackets when writing but just to clarify that when you wrote:

“As for Heiderscheit’s paper, I agree with his recommendation that you should increase your cadence IF YOU’RE OVERSTRIDING.”

Heiderscheit’s recommandation is “that you should increase your cadence” (from the context it is: over your preferred cadence) – period – in his paper “Effects of Step Rate Manipulation on Joint Mechanics during Running”. The qualification about doing it if you’re overstriding is your recommendation.

Overstriding is a poorly defined term, but from what I have seen it is most closely related to “excessive horizontal breaking force when the foot lands”.

I have recorded many three axes accellerometer readings on runners but has never seen an absent horizontal breaking peak, but I can see that my average peak breaking force (measured close to my center of mass) was reduced by 40 % by going from 173 to 180. With your cadence at slow speed I would say that you are overstriding just from your cadence.

So with

1) Less perceived effort

2) No metabolic cost

3) Feeling of less impact

4) Less breaking force

I had all the reasons I needed to change from 173 to 180 – and I agree that 180 might not be my optimum number, but it is better than 173. (I do not know at what cadence I started, but it was probably close to yours according to my wife!).

@David: I’m sincerely happy to hear that you’ve had success at 180. As I said to Geordie above, I have no doubt that aspiring to 180 can help many, many people. What I’m questioning is whether it makes sense as a universal prescription. If you were two feet taller and running half as fast as you do now, do you think the exact same cadence would be the right one?

@Jørn: I’m happy to discuss and debate — that’s what the blog is for! I’ve spoken to Heiderscheit and discussed this issue in detail with him. I can assure you that he does not believe that there is anything special about 180 as a cadence. He believes that cadence is individual, depending on the body morphology and pace of any given runner.

I find it hard to take seriously your argument that Heiderscheit’s paper is intended to apply to ALL runners, not just those who are overstriding. Do you seriously believe that, because of a study on some beginner runners in Wisconsin, Haile Gebrselassie should try to increase his cadence by 10%? Why would a runner who’s not overstriding want to increase his or her cadence?!

“With your cadence at slow speed I would say that you are overstriding just from your cadence.”

This is really the crux of your argument. Allow me to break it down:

(1) You believe my cadence is too low and should be increased.

(2) Why should I increase my cadence? Because I’m overstriding.

(3) How do you know I’m overstriding? Because my cadence is low.

(4) So in conclusion, my cadence is too low because my cadence is too low. Q.E.D.

Somehow, I’m just not convinced.

@alex

As a careful scientist Heiderscheit does not recommend anything. His conclusion (sorry for not mentioning Chumanov, Michalski, Wille and Ryan every time!) was:

“We conclude that subtle increases in step rate can substantially reduce the loading to the hip and knee joints during running and may prove beneficial in the prevention and treatment of common running-related injuries.”

Thus no qualifications with regard to types of runners and overstriding. It goes without saying that you cannot apply this increase to the same runner indefinitely.

The 5-10 % is what he investigated and where he could see benefits that were not offset by metabolic cost or perceived level of exertion. (As he points out the slight increase in perceived level of exertion at +10 % may be due to increased attentional focus).

The relationship between cadence and overstriding is trivial as shown in table 2 where the center of mass to heel distance at initial contact varies with a significant difference at each step from 11.4 cm to 7.0 cm when the cadence changes from -10 % to 10 %.

Thus low cadence = overstriding.

My argument was:

Instead of relying on your preferred cadence as something ingrained in you try to increase your cadence until the benefit of less loading is offset by increased metabolic cost or perceived level of exertion.

My experiment along these lines showed that I could increase my cadence from 173 to 180 running at 8.3 km/h without any metabolic cost and with a DECREASE in the perceived level of exertion while among other things reducing my peak horizontal breaking force by 40 %.

@Jørn: I fear we’re just going to have to accept that we’re arguing at cross-purposes, because what you write still has nothing whatsoever to do with the point of my post. I’ll sum it up one more time:

1. It is widely believed that a cadence of 180 is “optimal.”

2. The basis of this belief (for some but not all believers) is that Olympic-level runners are observed to run at a cadence of 180 or higher during their races.

3. My personal example shows that an elite distance runner who runs with a cadence of greater than 180 at Olympic race paces (e.g. 3:00/km) might also run with a significantly slower cadence at slower paces (e.g. 5:00/km).

4. The “representative” data from Weyand et al. shows that my cadence vs. pace curve is not unusual.

5. Therefore I conclude that the observation that Olympic distance runners race at 3:00/km with a cadence of 180 is insufficient evidence on which to recommend that joggers at 5:00/km should also aim for a cadence of 180.

Of course there are many other aspects to the debate about cadence, such as braking force, footstrike, injury risk, running economy, and so on. These are all interesting questions, and none of them are addressed in this post. Perhaps 180 really is the magical cadence for all paces and all runners — but if so, observing Olympic distance runners racing at that cadence isn’t the evidence that shows it.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N5tcgpHIaw0

What is the cadence here at 2:46 per km?! 4:12-4:32 is a good shot of him turning over at incredible speeds for an end of a half marathon.

Hi Alex,

Have commenced a personal experiment to see if my cadence has changed from before I made some improvements (about 3 years ago) to my running technique and personal best times compared to afterwards. In some old video I found, at 5 min km pace 12kph I was striding at about 154 at 4 min km pace 15kph this had increased to 180. In the next week I will take some video and see if anything has changed and report back. I’m thinking now that I’m a bit stronger and faster that I might stride slightly slower at 4min km pace … we’ll see.

Thanks for the informative read and lively discussion.

Brian

“3. My personal example shows that an elite distance runner who runs with a cadence of greater than 180 at Olympic race paces (e.g. 3:00/km) might also run with a significantly slower cadence at slower paces (e.g. 5:00/km).”

Are you an elite distance runner? Otherwise I don’t understand your conclusion.

I believe that its normal that cadence varies with speed but maybe the variation should be less for most people? If you use lower cadence it is likely that you either moves to much vertically or land with your foot in front of your body I would say, which both puts more stress on your body.

Furthermore it seems too me that the Weyand study subjects are average runners and not elite runners so it just shows how the average runner increase and decrease their cadence according to speed. They should do a similar study with elite runners and compare the results because one assumes that an elite runner uses way better technique than the average runner.

@Patrik

“Are you an elite distance runner? Otherwise I don’t understand your conclusion.”

I didn’t intend to compliment myself — perhaps I should have said “well-trained” instead of “elite.” My best times are 3:42, 8:00 and 13:52. Of the other runners shown on my graph, Gorski is a 3:39 1500 runner, and Burfoot is a former Boston Marathon champion. I see no reason to assume that the change in cadence as a function of speed that we all display is somehow unique to “average” runners.

I did a little research using youtube clips and windows live movie maker that lets you play video frame by frame which was really needed because the intervals of elite athletes jogging are very short (unlike their racing). I got these numbers: Sammy Wanjiru 160, Bekele brothers 170, Haile Gebrselassie – almost 180. I used the following videos:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CwJRWlDLGCg

around time 2:43

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yuf80lOyoV0

time 4:44

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X6Q_TIuf_ZI

time 0:25

I read JDaniels “Running Formula” around 12 years ago. I am a recreational runner, having run 1 yr in HS (400, 800), picked up Corporate Track in the mid 80’s which led me to weekend 5k’s, 10k’s, etc.

As a result of reading Daniels I tested my stride rate at easy pace: it was consistantly 160-166 spm. Tucked away in the back of my mind it took me around five years before I mastered the 180 at easy pace, and can now go to 185 – 190 at will, at easy pace. It changed the way that I run.

My stride is now, under and behind me, the push off and ankle extension being the source of the forward motion. I believe the change in form also helped to reduce arm swing and body rotation, by shortening the stride. At slow speeds on a tread mill, higher stride rates turn into more of a dance than a run; but the object is that as as stride rate increases, easy runs should become faster. Why would I wish to cut stride length to create an excessively slow pace?

Daniels makes basically this argument: the less steps you take, the more time you spend in the air. Due to gravity, the only way you can spend more time in the air, is to launch higher, which of course leads to a more stressful impact on landing. That is Daniels justification for improving stride rate, – for those with lower than 180 strides per minute, at any pace. It worked for me. I understand his point.

@Elise

That is because you are running incorrectly.

Bolt 100/200: ~260 cadence

Wariner 400: ~240

Rudisha 800: ~216

1500: ~200

5000/10000: ~180-190………the magic number! the one that jack daniels confused everyone about!

I love this article. I have been trying to change my cadence to hit the magic 180 and have found myself stuck in the 160s and have strongly suspected that cadence (and possibly landing spot) are affected by speed rather than the other way around. Being an older, slower “runner”, I have no intention of running 5 minute miles ever again. So the question becomes, am I over-striding if I, at 5′ 9″, am around 164 strides per minute at my standard 10 minute mile pace? I agree with someone that said height should also be taken into account where shorter people will naturally have shorter strides. I now think just focusing on landing spot through minimalist shoes (or barefoot) is a better strategy to eliminating over-striding. Of course, this is from a whopping week of experimenting so far so I may think entirely differently a few months from now.

Thanks for the information on the 180 cadence. I thought it was gospel till I read further into your article. See my article on cadence (for beginners) that are just getting started and looking to improve their running and form. http://slobtostud.com/what-is-cadence-running-statistics-explained/